Martin D, Grab F, Scofield C, Schurmann M, Stuart L, Grose C, Plant & Food Research

In this final article of the series about the Ideal vine study within the New Zealand Pinot Noir Programme, we take a plunge to try to answer specific questions that have been posed by wine industry professionals at various reviews, workshops and forums.

What does ‘Ideal vine’ mean?

We established a network of 12 trial sites in three New Zealand regions from 2018 to 2022 in a search for individual vines that produced viable commercial yields and wines of composition comparable to that of wines made with ‘Icon’ label vines. A commercially viable minimum Pinot noir yield was defined at the start of the programme by the Industry Advisory Group as 9 tonnes per hectare which, at the average planting density of the study network, broadly equated to 2.1 kg per vine or 1.75 kg per metre of row length. Grape composition targets were derived from a random subset of the vines grown in Icon vineyards. Vines that achieved the Icon grape quality specification, at yields above 1.75 kg/m were considered the outstanding performers or Ideal vines within the study population.

Is there a relationship between Pinot noir vine yield and wine quality?

The answer is both yes and no. At a population level, there are more vines within a block that achieve a high-quality standard when yield is low than when yield is high. However, at an individual plant level, and depending on the vineyard and season, 10–30% of vines achieve both good yields and Icon quality.

What does an Ideal vine look like?

The question is not easy to answer because we did not find a single vine in the entire 993 (vine x year) combinations in the study that met the Ideal definition more than three years in five. This was, however, partly due to crop-thinning strategies adopted by the Icon vineyards which kept many vines below the commercial yield target. Nevertheless, we can propose that an ideal Pinot noir vine in New Zealand conditions should have some or all of the following attributes:

Vine size

Many of the Ideal vines were small (i.e., of lower capacity) as a result of higher planting densities and lower fertility soils. This is probably because the interannual swings in vine performance are within a narrower and lower range when the vine is small compared with larger vines. Ideal vines probably hit a sweet-spot combination of bud load that matches both the dormant vine’s capacity and the upcoming season’s ripening potential. This would appear to happen more frequently when the vine is small.

Canopy density

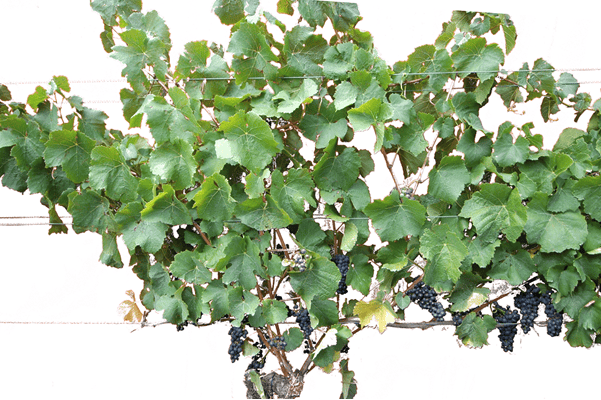

Ideal Pinot noir vine canopies were very open. Shoot vigour was moderate to low, with spacings of 10 to 12 shoots per metre of fruiting wire. The vast majority of shoots on a vine (> 80%) had a diameter between 6 and 10 mm at the third internode (i.e. there were only one or two stunted or highly vigorous shoots per vine). An example of an Ideal vine canopy is provided in Figure 1. Shoot lignification was well advanced at véraison and complete (at least visually) at harvest.

Figure 1: Example image of an Ideal vine at harvest in 2019 (background has been digitally removed).

Optimum ratio of yield to leaf area

The majority (67%) of In-Spec vines had an estimated 0.7–1.7 m2 of leaf per kg of yield with a mean value of 1.1 m2 per kg. That represents two smaller bunches (150 g) on a shoot with 20 leaves, the largest of which is about saucer-size.

Ripening speed

Fruit typically ripened well and quickly such that a TSS of 22–23° Brix was achieved without obvious berry dehydration or shrivelling. Because Pinot noir berry skin integrity has a finite lifespan, fast (active) ripening allows longer hang-time (after berry sugar loading has stopped) before shrivelling sets in.

Berry size

Ideal vines had a mean berry weight below 1.2 g but a yield greater than the commercial threshold of 1.75 kg/m of row length. This means that vines needed to have a higher number of smaller berries rather than a lower number of larger berries for a given yield. Small berries not only resulted in a higher marc:wine ratio but they also had higher phenolic content per unit area of skin and better acid, YAN and potassium statistics. In vintages that had large berries (2018 and 2022), wine colour was as much as three-fold lower than in high-colour vintages like 2019 and 2021.

Yield

This is obviously the big question surrounding the Pinot noir Ideal vine work. What we can say is that at an individual vine level, the optimal range at which Icon grape quality can be regularly achieved is between 1.5 and 2.75 kg metre. Below 1.5 kg there would appear to be little quality gain whereas there was a rapid drop-off in quality above 2.75 kg. This yield range requires that all the other Ideal vine attributes are also met – especially that of maximum berry size.

Should we try to manipulate canopy with water usage down to a fine art?

In general terms, the Ideal vines were all irrigated and showed no visible or measurable signs of lengthy water limitations in any of the vintages. Carbon isotope testing of the wines showed only minor differences in overall seasonal vine water status between years, with vintage means being more negative than the threshold water deficit value of −27.0. While short-term vine water deficits cannot be completely ruled out, it seems unlikely that the entire study network of 12 vineyards would be concurrently affected in a similar way.

What is the role of timing and severity of leaf plucking on quality?

The vast majority of the vines in the study had well-exposed bunches from a combination of low vigour, widely spaced shoots and leaf plucking. We could not find any differences between Ideal or non-ideal vines. Analysis of quercetin glycosides in wine (a key indicator of fruit exposure to UV radiation) was strongly influenced by vintage but not by vineyard (and therefore not by management differences). In more general terms, early leaf plucking increases berry tannin (but not colour) while late leaf plucking can improve berry colour if sunshine hours are limiting during ripening.

Are current management practices fit-for-purpose?

The challenge isn’t really the management practices we use, but the scale at which they are applied. A management approach may work for one vine but not the one next to it. It’s also not a constant from year to year as what may work one year may not the next. The viticultural practices generally used by New Zealand’s top-end Pinot noir producers, especially with regard to yield management, provide an effective means of ensuring the majority of vines in the block meet a high-quality standard. In the future, we can seek to develop and operationalise vine management strategies that allow individual tailoring of bud load to the actual winter reserves of each vine (which depend on the previous season’s yield and growing conditions and cane selection on the vine in question).

How do you best forecast yield and thinning needs?

For Pinot noir, very early véraison provides the optimal time to assess yield because the final bunch weight is more predictable than at pre-bunch-closure and manual green thinning reduces bunch-to-bunch variation in phenology. Gains in sugar ripeness are less marked if thinning is carried out much earlier or later than this. We are currently developing harvest bunch weight prediction models for Pinot noir based on flowering temperatures which will assist in yield estimation and thinning decisions.

What did we learn about crop thinning?

One of the key points is that it is very hard to achieve a target bunch number/yield on the majority of vines in a block. Even in the most meticulously managed vineyards, where manual crop thinning happened multiple times throughout the season, vine-to-vine yields were surprisingly variable. In the best case, about 20% of the vines didn’t have enough crop and about 30% of the vines had too much relative to the mean or target yield. The other key point was that berry size and season were most influential for berry quality. Neither of these two factors is altered by crop thinning, which is probably less beneficial to quality if berry size and season are favourable.

Is there anything we can do in the winery if berry monitoring tells us that quality potential might be lower?

If pre-harvest testing shows that colour/phenolic development in the berries and ripeness are adequate then “saignée” to compensate for a higher than desired berry size is an effective option. A proviso is that the saignée volume should remain below about 15% of the must volume. If pre-harvest sampling shows that colour/phenolic development is low then, with the right processing equipment, an option would be to sort intact destemmed berries to separate the largest size group (above 1.2 g) using a vibrating table system with an appropriately sized grill. Both saignée and sorting approaches assume that there is an alternative product stream able to accept the culled juice/fruit.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the 11 participating wine companies for providing the study vineyards and grape samples. This type of research is made possible by the intellectual contributions and passion of winemakers and viticulturists. For more information about the programme and these research aims, including full reports and methods used, please visit the members’ section of nzwine.com.