Dr Yusmiati Liau, Bragato Research Institute

The findings from this small research project indicate possible moderate resistance to key fungicide groups within some powdery mildew populations in Marlborough and Hawke’s Bay vineyards, emphasising the importance of rotating chemical groups and monitoring for signs of increased resistance.

Why fungicide resistance matters

Powdery mildew (PM), caused by the fungus Erysiphe necator, is a persistent problem for grape growers worldwide. If untreated, PM can cause significant loss, as even minor infections of berries can have a detrimental effect on wine quality.

To manage PM, growers use a combination of multi-site inhibitor fungicides such as sulphur or copper, as well as modern single-site inhibitor fungicides such as Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors (SDHIs), Quinone Outside Inhibitors (QoIs), and Demethylation Inhibitors (DMIs). However, the PM pathogen is highly adaptable and can quickly develop genetic variants to survive fungicide application. Regular monitoring allows developing resistance to be detected early so that resistance management can be implemented to preserve the effectiveness of these fungicides.

Multi-site fungicides like sulphur and copper are tough for fungi to outsmart but are less effective than modern synthetic fungicides. Multi-sites fungicides attack multiple parts of the fungus’s metabolism, making it hard for the fungus to develop resistance. For a fungus to survive these treatments, it would need to mutate in several different genes at once, which is unlikely. In comparison, single-site inhibitors, such as QoIs, DMIs, or SDHIs target a specific biochemical pathway within the fungus. Because of this, the fungus often only needs a single genetic mutation to resist the fungicide.

In New Zealand, data on the extent of fungicide resistance in PM is limited. Research from nearly a decade ago documented resistance to some DMI fungicides like myclobutanil and penconazole, and a high rate of resistance to the QoI fungicide trifloxystrobin. A follow-up study in 2017 found no resistance to SDHIs like fluopyram. However, the PM pathogen has shown the capacity to develop resistance within just a few years. The development of resistance to the same fungicides in several other crop pathogens has also been documented. Therefore, improved monitoring tools and regular surveys of fungicide resistance in grapevine PM and are essential.

What we did in this project

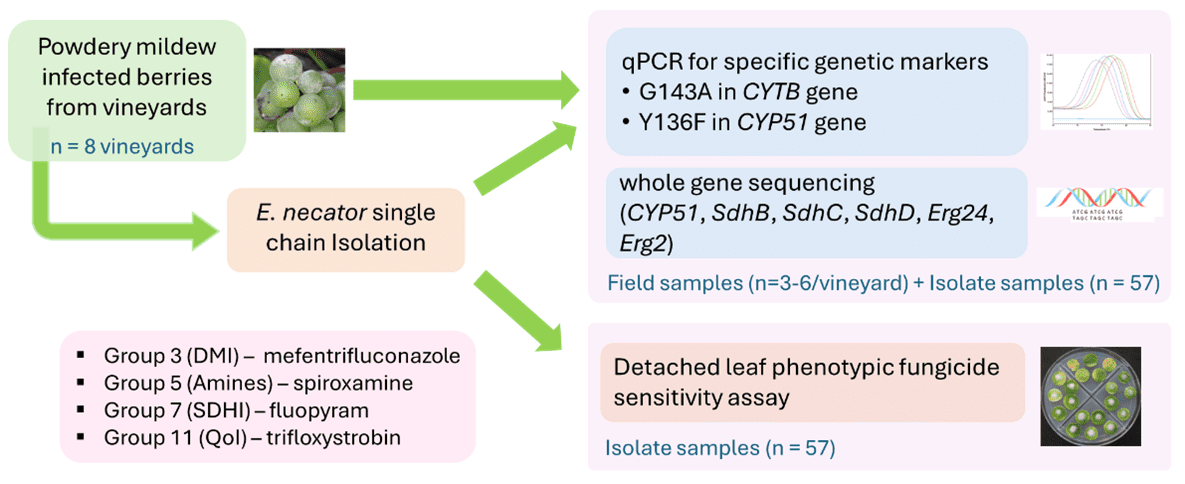

Bragato Research Institute, in collaboration with The New Zealand institute for Bioeconomy Science Limited (BSI), carried out a pilot survey in early 2025 to assess PM fungicide resistance in two key winegrowing regions in NZ, Marlborough (2 vineyards) and Hawke’s Bay (6 vineyards). The study combined two parallel work streams:

- Traditional phenotypic testing (detached-leaf fungicide assays) carried out by BSI, Plant & Food Research Group

- Molecular diagnostics for specific mutations and whole gene sequencing carried out by BRI.

The aim of this project was two-fold; firstly, to develop tools for early and rapid detection of fungicide resistance developing in vineyards. Secondly, provide an up-to-date snapshot of PM fungicide resistance in NZ vineyards, building on research undertaken in 2015 and 2017.

Based on the spray diary data from recent years, we focused on three commonly used fungicides:

- Group 3 (DMIs) – mefentrifluconazole

- Group 5 (Amines) – spiroxamine

- Group 7 (SDHIs) – fluopyram

Additionally, a well-established genetic marker of fungicide resistance to Group 11 (QoIs) (G143A in CYTB gene) was screened.

Figure 1. Workflow of sample collection and phenotyping and genotyping methods

Detached leaf assay is regarded as the gold standard for phenotypic fungicide sensitivity status, however it is labour intensive, time-consuming, and poorly suited for routine and rapid screening. A genotypic method on the other hand offers a faster more efficient solution, by identifying specific genetic changes in the pathogen genome linked to resistance. In addition to the G143A mutation, a Y136F mutation in the CYP51 gene has been associated with DMI resistance. A G169D/S mutation in the SdhC gene and the H242R/Y and I244V variants in the SdhB gene have also been associated with SDHI resistance. No genetic marker has been identified for Group 5 fungicides.

In this project, we established a targeted assay to detect the G143A and Y136F variants. Additionally, we conducted a comprehensive assay using whole gene sequencing to screen for variants in SdhB, SdhC, SdhD (Group 7), as well as Erg24 and Erg2 (Group 5). Given the reported weak correlation between the Y136F mutation and DMI phenotypic resistance, we also sequenced the entire CYP51 gene.

Key Findings

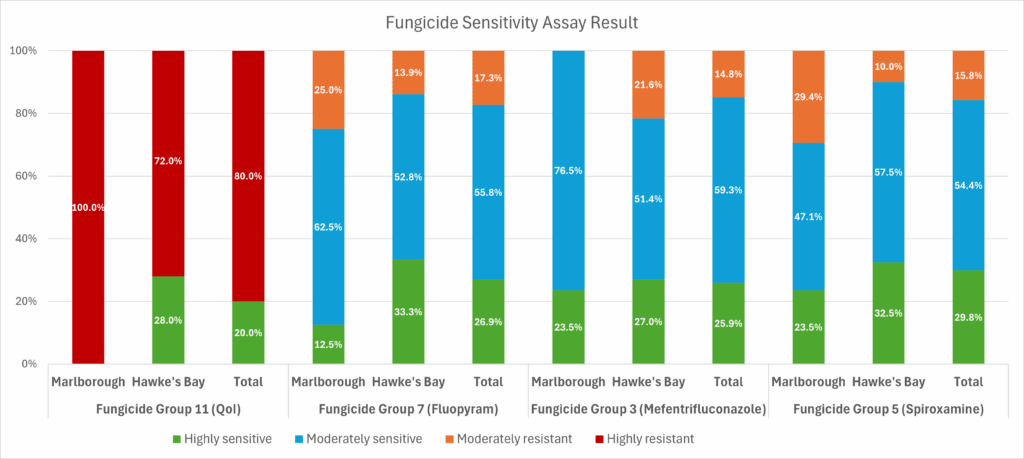

For QoIs, we observed a complete resistance profile among samples from the two Marlborough vineyards based on the G143A mutation, while Hawke’s Bay samples were more mixed with only one vineyard showed full resistance. Ongoing monitoring of this variant, especially outside of Marlborough is recommended for regular monitoring of resistance to this fungicide group.

For DMIs, a known genetic marker, Y136F in CYP51 gene was found in all samples, but it did not lead to strong resistance to newer DMIs like mefentrifluconazole with moderately resistant isolates reported for only 14.8% of the isolates, all from Hawke’s Bay. Therefore, this genetic marker alone has limited utility for effective resistance monitoring in this group. No other notable variants were detected in the CYP51 gene. Further work is needed to identify better genetic markers, including looking at CYP51 gene copy number or expression.

For amine and SDHI fungicides, 16–17% of samples showed moderate resistance, with some vineyards having relatively higher EC50 values. No previously reported or other notable variants were found among the five target genes. Further work is recommended for continued monitoring of resistance in these fungicide groups and identification of useful genetic markers.

Currently, the G143A mutation in the CYTB gene is the only reliable genetic marker to predict fungicide resistance in PM for QoI fungicides. For other fungicide groups, further research is still needed.

Figure 2. Fungicide sensitivity categories for four fungicide groups. Categories for Fungicide group 11(QoIs) were based on G143A status, and categories for the other groups were based on fungicide sensitivity assays

Implications for Vineyard Management

Within our relatively limited sample size from Marlborough vineyards, the G143A mutation that underpins QoI resistance is now prevalent in the Marlborough PM population, indicating complete resistance to QoI fungicides. In Hawke’s Bay, QoI resistance is mixed, so short-term use may still be viable, but only with caution and rotation.

For DMI fungicides, the Y136F mutation was found in all samples, suggesting historical overuse. However, newer DMIs like mefentrifluconazole remain effective. To preserve their efficacy, growers should rotate with unrelated fungicide groups such as SDHIs, amines, or sulphur. Older DMIs (e.g. myclobutanil, penconazole) may be less reliable, though their use has declined. Currently, mefentrifluconazole is the primary DMI used in NZ vineyards.

SDHIs and amines show low levels of moderate resistance and remain viable options. These should be used as part of an integrated program, not in isolation. Always follow label resistance-management guidelines—limit the number of SDHI applications per season and avoid consecutive sprays with the same mode of action.

Summary

This project offers a small-scale update on PM fungicide resistance in NZ vineyards. QoIs (Group 11) resistance is widespread in Marlborough, while moderate resistance is observed in Groups 3, 5, and 7 for the two regions, with no high-level resistance detected. Ongoing research and broader monitoring are essential to manage evolving resistance, identify better resistance markers and ensure sustainable disease control.

About the project

This one-year project is a collaboration between Bragato Research Institute and The Bioeconomy Science Institute, Plant & Food Research Group. It is funded by the New Zealand Winegrowers levy. We would like to acknowledge the project team, Yusmiati Liau, Amy Hill, Bhanupratap Vanga & Darrell Lizamore (Bragato Research Institute), Robert Beresford, Peter Wright, Peter Wood & Dion Mundy (The New Zealand Institute for Bioeconomy Science). In addition, we would like to acknowledge the vineyard managers who kindly allowed samples to be collected from their vineyards to support this research.